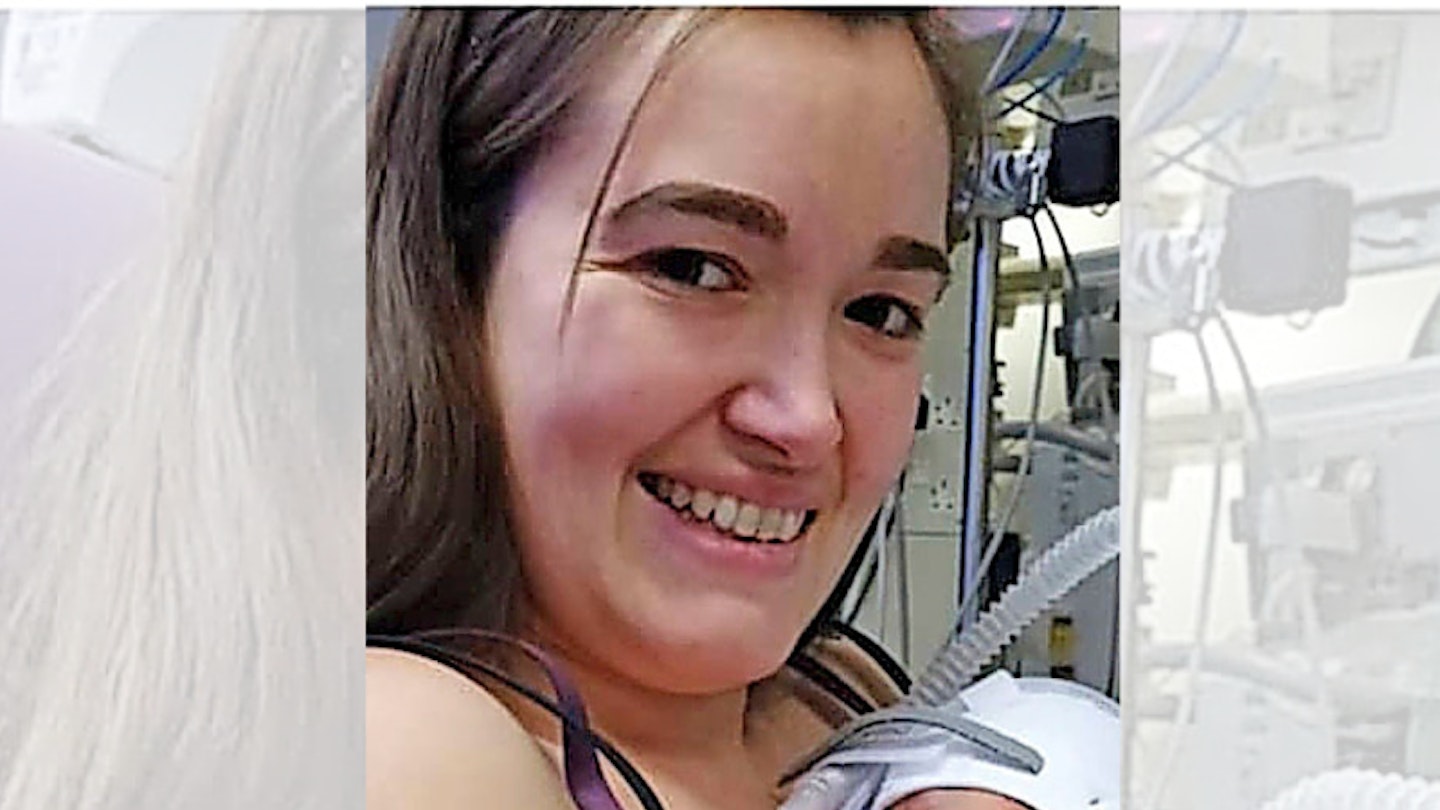

I just wanted a baby. But how much heartache would I have to endure? By Belynda O’Brien, 31

I pressed my eyes closed and said to myself: ‘Third time lucky.’ Then I opened them and gasped.

I thought: I don’t believe it!

My partner Dean and I had been trying for a baby for five years before turning to IVF for help.

We’d suffered a miscarriage and one failed round, but this time it had worked.

I was pregnant.

We’d gone against the advice of our consultant and had two embryos implanted. While it increased the chances of getting pregnant, it also raised the risk of miscarriage.

But I pushed that thought to the back of my mind as I started to think about the little life growing inside me.

I made cards to tell our families, and everyone was thrilled for us.

But a few weeks later, on a weekend trip to London, I went to the toilet and discovered I was bleeding.

When I came back out to find Dean, he said: ‘What’s happened?’

‘I think I’ve lost the baby,’ I told him.

He hugged me.

‘We don’t know that for sure,’ he said.

But after all we’d been through, it was hard to hold on to hope.

We managed to get an appointment at our clinic for the Monday morning, leaving us with an agonising wait over the weekend.

The clinic’s receptionist told me to try to relax, and that it might not be a miscarriage.

But I felt sure it was.

During the weekend, the bleeding showed no sign of stopping.

In the end, Dean said: ‘I’m worried about you, let’s go to hospital.’

I had some blood tests and went home after being advised it probably was a miscarriage and to rest.

When I phoned for the results later, a nurse said: ‘That’s strange. Your hormone levels are sky high, which does indicate a pregnancy.’

I went back for a scan which revealed a heartbeat. A nurse explained that I’d probably been pregnant with twins but had miscarried one. It was known as vanishing-twin syndrome.

I’d lost one baby, but I still had the other and that gave me some comfort.

As the weeks went on, my bump started to grow and once I’d passed the 12-week stage, I began to relax.

By the time I reached 15 weeks, I decided it was time to start getting ready for our new arrival, and Dean and I bought a cot and Moses basket.

But just a week later, at a routine scan, there was devastating news.

‘I’m sorry,’ the sonographer said. ‘There’s no heartbeat.’

I went home, thought about the empty Moses basket at Dean’s mum’s house, and wept.

I would have to deliver the baby and I felt terrified, but the staff at the hospital were so kind and supportive.

I delivered my little one and afterwards, we were allowed to spend time with the baby.

‘We’re 90 per cent sure she’s a girl,’ the doctor said, ‘but she’s so small we can’t be sure.’

We chose a unisex name and settled on Reagan.

In the weeks that followed, we struggled to come to terms with Reagan’s death. Trying again and going through another round of IVF was the last thing on our minds.

But the rules around the storage of embryos at the clinic were changing and less than six months after we lost Reagan, they called.

If we wanted another round of IVF with our embryos it had to happen straightaway.

So we went ahead.

We were still raw from losing Reagan and when a pregnancy test came back positive, I felt terrified.

‘I can’t cope with losing another baby,’ I told Dean.

‘It won’t come to that,’ he said.

But at our seven-week scan, the sonographer ran the scanner over my belly and frowned.

And my heart sank.

I thought: It’s happening again…

But then she said something unexpected.

‘I’ve found a heartbeat,’ she told us. ‘And another one.’

I looked at Dean and his face was a picture.

We were having twins again.

I didn’t want to get my hopes up in case something went wrong, but at 16 weeks — just past the point when we lost Reagan — we began to allow ourselves to feel excited.

I went shopping for all my baby bits, thinking I had plenty of time to get ready.

But at 26 weeks my waters broke.

‘It’s too soon,’ I said.

Dean drove me to the local hospital. But as the babies were so premature I was taken by ambulance to another hospital.

A few hours later I gave

birth to a baby boy. We named him Cobie.

Doctors expected his twin to follow soon after but there were complications, and it was 10 hours later when Jake arrived by Caesarean.

Because the boys were so premature, they had to stay in hospital after I was discharged and at three weeks old, Jake was transferred to Great Ormond Street in London for heart surgery.

With the boys in different hospitals, Dean and I split our time between them. It was a nightmare and we were exhausted. I thought at any minute I might lose one or both of them.

But, at four months, we were able to take Cobie back to our home in Kent.

We tried to enjoy life as new parents, but we couldn’t while Jake remained in hospital.

Finally, two months on, we brought him home too.

We were so happy, we didn’t mind the sleepless nights that followed.

After all we’d been through, we had our family at last. And I was happy with that.

But when the boys were two, I realised I’d missed a period.

I didn’t think I could get pregnant naturally, but I did a test anyway and I couldn’t believe the result.

‘How is this possible?’ Dean asked.

‘I don’t know,’ I gasped.

It had taken over seven years, but finally I’d conceived naturally.

‘How on earth will we cope with two babies and a newborn?’ I said.

‘We’ll get through it,’ Dean replied.

This time, I had a planned Caesarean at 37 weeks and welcomed a baby girl who we named Indie.

Cobie was instantly besotted with her. It took Jake a few months to warm up to her but once he did, he adored her.

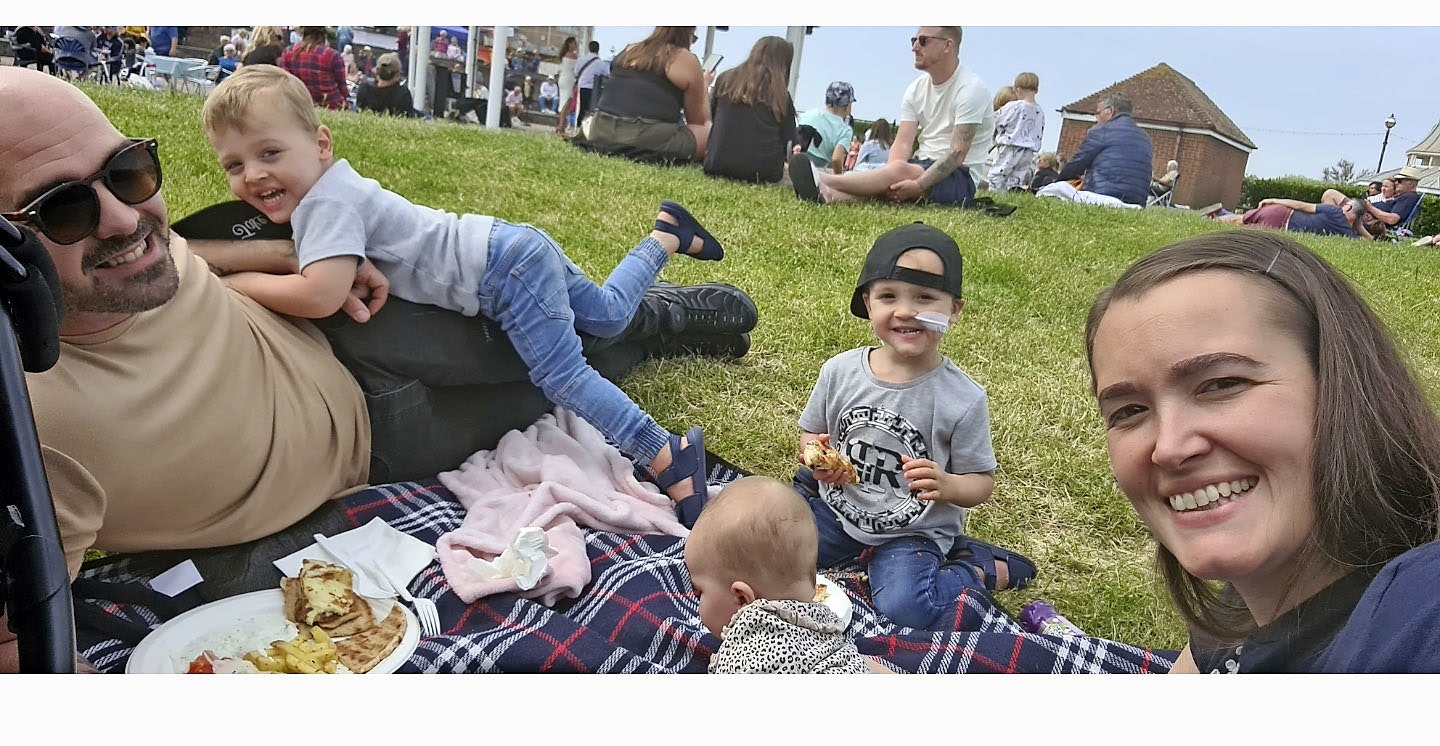

Now, against all the odds, we are a family of five.

I still can’t really believe it.

Our road to becoming parents was such a long and difficult one and because of that we’ve decided to donate our leftover frozen embryos. We know how hard fertility issues are, so we want to help other couples in our situation.

If we can make it easier for them to become parents, that would be brilliant.